Wilde’s Salomé

Ross e.113

Just in time for the “Women Writing Decadence” conference that will take place in Oxford during July 2018, this Treasure features a play that epitomises the decadence of the 1890s. When The Times reviewed Oscar Wilde’s play Salomé on the 23rd of February 1893, it was described as “an arrangement in blood and ferocity, morbid, bizarre, repulsive and very offensive.”

Although the story of Salomé had fascinated Wilde from the early 1880s, he only began writing his one-act play in Paris in 1891 and finished it the following January in Torquay. Wilde’s first attempt at writing in French, the play inspired the talented Parisian actress, Sarah Bernhardt, who planned to produce it in London during 1892. Bernhardt herself, at whose feet Wilde had famously strewn white lilies, was to play Salomé. Whilst in rehearsal, however, Salomé was banned by the Lord Chamberlain’s licensor of plays due to an old law that prohibited the depiction of biblical characters on stage.

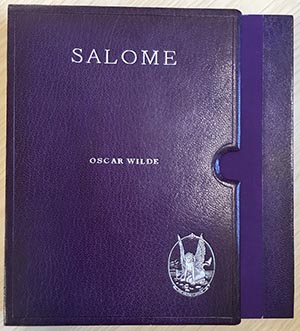

Ross e.109 Tyrian Purple Box and Binding

Oscar Wilde changed the slant of the traditional biblical story of Salomé but the essential plot remains the same. Salomé, the daughter of Herodias and stepdaughter of the tetrarch Herod Antipas, demands the head of Jokanaan (aka John the Baptist) on a silver platter as a reward for performing the dance of the seven veils for her step-father.

Wilde’s interpretation of the story places the emphasis on Salomé as a hyper-sexualised and empowered woman, using his extensive understanding of nuance in the French language to heighten the drama. Salomé, enraged that Jokanaan has rejected her impassioned advances, uses her feminine guile to put Herod in a position where he has no choice but to have Jokanaan killed. The climax sees Salomé kiss the bloody mouth of the decapitated Jokanaan before she, in turn, is killed on Herod’s orders. Wilde’s version of the story has proved fertile ground (as we shall see below) for theatrical producers and illustrators.

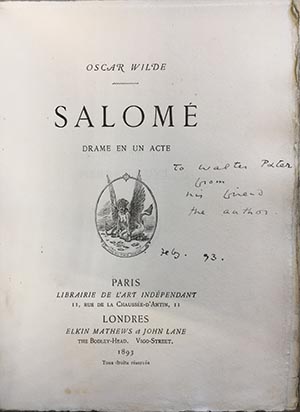

Ross e.109 Dedication to Walter Pater

Although there was a ban on depicting biblical figures on the stage in the late 19th century, there was no such restriction on printed works. Salomé was published for the first time in the original French in Paris in 1893. Oscar Wilde had a hand in the design of the book, choosing Tyrian purple for the covers, to match the gilt hair of his lover, Lord Alfred Douglas. Oscar Wilde’s son Vyvyan Holland commissioned the purple morocco leather box and slip-case shown above to match the covers of the Univ copy.

As soon as the book was published, Wilde inscribed several to supportive friends. One of the copies in the Robert Ross Memorial Collection is dedicated to Walter Pater, the essayist and literary critic. Wilde and Pater did not always have an easy relationship and, although Wilde was initially impressed by Pater, they were later known to be privately critical of each other’s work. Wilde also sent copies to George Bernard Shaw, Algernon Swinburne, and the artist Charles Ricketts.

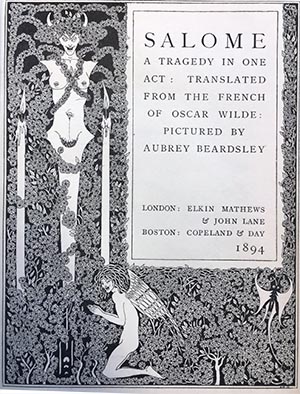

Ross e.113 Title Page

Despite the play still being banned from the British stage, Wilde determinedly pushed ahead with publication of an English translation during 1893. It appeared in early 1894, with the telling omission of the translator’s name on the title page. Initially Wilde asked Alfred Douglas to undertake the translation, but he had underestimated his lover’s grasp of the French language to such an extent that the result was unpublishable. In order to avoid a tantrum, Wilde offered an olive branch and Douglas is credited before the text as “the translator of [his] play”.

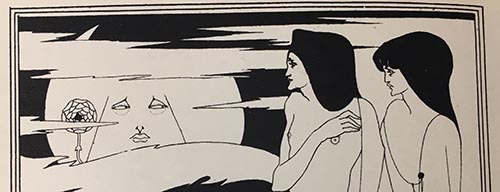

As well as being the first English translation of Wilde’s play, this edition is also the first to be illustrated. In April 1893 the Studio, a fine and decorative arts magazine, published a drawing of Salomé holding the head of John the Baptist. The young and little-known artist was Aubrey Beardsley. The drawing piqued Wilde’s interest, and the publisher, Elkin Matthews, commissioned Beardsley to illustrate Salomé. The images he produced are some of the most widely recognised by a British artist of the fin de siècle. Beardsley frequently made use of dark humour in his works, and Oscar Wilde himself has been parodied as a rather sad moon in the frontispiece.

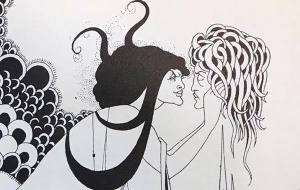

Ross e.113 Aubrey Beardsley Illustration

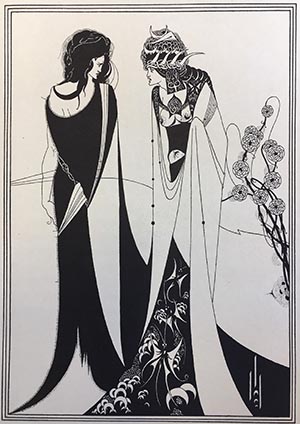

Ross c.14 John and Salomé

In true decadent style, two of Beardsley’s drawings for Salomé were deemed too risqué for publication; one was bowdlerized, and the other replaced with another, more respectable, image which had little relevance to the play. The image titled John and Salomé was thought to show the female figure as too dominant and assertive, whilst John the Baptist takes on some more traditionally feminine characteristics.

The theatrical premiere of Salomé took place on 11 February, 1896; not in London, as first planned, but in Paris. By this time, Wilde’s career had taken a sudden, disastrous, turn, leaving him bankrupt and imprisoned on charges of gross indecency. A previous Treasure, Oscar Wilde’s 1895, outlines his downfall.

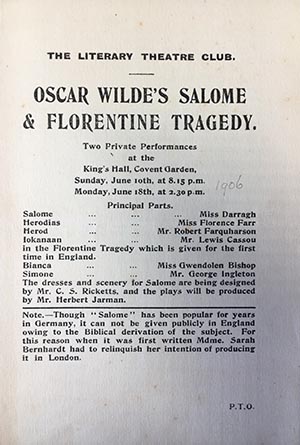

Ross Env. e.116 “Private” Performances Flyer

Salomé was not performed in England until May 1905, well after Wilde’s death in December 1900. Only allowing members of theatrical clubs to buy tickets circumvented the law, which still prohibited public performance. The flyer shown here includes a form that allowed members of The Literary Theatre Club and their guests to book tickets to the “private” performance. In order, perhaps, to increase demand for the tickets, Sarah Bernhardt’s name is dropped into the flyer, even though she had nothing to do with this performance.

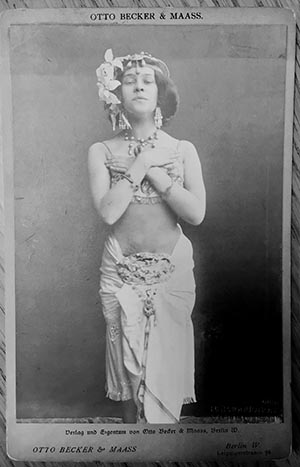

Oscar Wilde’s Salomé captured the mood of the fin de siècle and was popular across the continent. The Robert Ross Memorial Collection holds two photographs of a performance in Berlin in 1903 (pictured below). As in England at the time, Prussian law barred public performances of the play until September 1903, but in November of that year Max Eisfeldt played Jokanaan with Tilla Durieux as Salomé at the Neues Theatre, Berlin.

Wilde’s Salomé has continued to be a popular subject for illustrators, theatre producers, and translators; other examples from the Robert Ross Memorial Collection will be high-lighted in future Treasures.

Ross Box 1.2.i Salome

Ross Box 1.2.ii Tilla Durieux as Salome

Ross c.14 Beardsley, A. (n.d.). Aubrey Beardsley’s illustrations to Salome [by O. Wilde. On Japanese vellum].

Ross e.109 Wilde, O. (1893). Salomé : Drame en un acte. Paris, Londres: Paul Schmidt.

Ross e.113 Wilde, O. (1894). Salome : A tragedy in one act. London : Boston: Elkin Mathews & John Lane ; Copeland & Day.

Ross Env. e.116 Flyer (2 leaves, folded) produced by the Literary Theatre Club advertising two private performances of ‘Oscar Wilde’s Salome & Florentine Tragedy’ at King’s Hall, Covent Garden on 10th and 18th June [1906].

Ross Box 1.2.i Photograph (postcard) showing Salomé performed by Tilla Durieux as Salomé and Max Eisfeldt as Jochanaan. Photograph by: ‘Zander & Labisch’.

Ross Box 1.2.ii Photograph (mounted on card) showing Tilla Durieux as Salomé. Berlin. Nov. 1903. Neues Theater.’ Photographer: ‘Otto Becker & Maass… Berlin W. Leipzigerstrasse 94…’

Select Bibliography

Edwards, O. D. (2012) “Wilde, Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills (1854–1900), writer.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 15 Jun. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/29400.

Ellmann, R. (1987). Oscar Wilde. London: Hamish Hamilton.

Frankel, N. (2000). Oscar Wilde’s decorated books. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Hoare, P. (1998). Oscar Wilde’s last stand: Decadence, conspiracy, and the most outrageous trial of the century (1st North American ed.). New York: Arcade Publishing.

Millard, C. (1967). Bibliography of Oscar Wilde (New ed.). London: Rota.

Samuels Lasner, M. (1995). A selective checklist of the published work of Aubrey Beardsley. Boston: Thomas G. Boss Fine Books.

Tydeman, W., & Price, S. (1996). Wilde: Salome (Plays in production). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Published: 19 June 2018

Further selected Univ Treasures are detailed below or explore the whole collection on our News and Features Treasures pages.