A Victorian common room

Univ’s archives are lucky enough to hold a few photograph albums dating from the 1850s to the 1870s. Most of them were compiled by undergraduates from this period, but there is one album from that date which stands alone. This contains photographs of our Fellows from this period. We do not know how, when or why it was created, but it survives as a very precious record of what our Victorian Fellows looked like. For this month’s Treasure, then, we include a selection of images of Fellows from this album.

Charles Frederick Plumptre

We start off with Charles Frederick Plumptre. Plumptre spent his entire adult life at Univ: he came up as an undergraduate in 1813, was elected a Fellow in 1817, and then Master in 1836, which post he held until his death in 1870. Plumptre was a shy man, and had a rather austere manner, as this photograph suggests. However, he succeeded in keeping the College together during a period when Oxford underwent major reform, and he himself did much to modernise Univ from within. He was also a supporter of the study of science at Oxford, playing a leading role in the creation of the University Museum.

Travers Twiss

Travers Twiss came up to Univ in 1826 and was a Fellow here from 1830–63. Having started out as a tutor in Greek and Latin, Twiss became a lawyer, successfully practising in the ecclesiastical and admiralty courts, but also acquiring a reputation in the field of international law. He married in 1862, and was knighted in 1867, but then his life was turned upside down. A blackmailer circulated dark rumours about Lady Twiss’s sexual past, and in 1872, Twiss sued him for libel. Within a few days, Lady Twiss fled abroad, abandoning the case, and effectively admitting her guilt. Twiss had to resign all his public offices, and spent the rest of his life in scholarly retirement (he lived until 1897), cutting off all his links with old friends.

William Fishburn Donkin

William Fishburn Donkin originally came up to St. Edmund Hall in 1832, but then got a Scholarship at Univ in 1834. He was a Fellow here from 1836–43, after which he served as Savilian Professor of Astronomy. Nevertheless, he continued to teach Maths and Logic to our undergraduates for several years after that date. Arguably he was the first scientist in the modern sense of the word to become a Fellow of Univ. He was also a keen musician. Donkin was much loved and respected by his contemporaries, but, as may be deduced from his gaunt appearance in this photo, he suffered greatly from ill health and he died in 1869 aged only 55.

Arthur Stanley

Arthur Stanley, seen here deep in a book, was an undergraduate at Balliol, but then became a Fellow of Univ from 1838–51. Stanley was one of the finest and most charismatic tutors of his age. With Plumptre’s evident support, Stanley radically improved the academic performance of the College. He was also one of the chief campaigners for the reform of Oxford in the 1840s and 1850s. Stanley later a leader of the liberal movement in the Church of England. He was an especial favourite of Queen Victoria, who shared his liberal beliefs, and in 1864 she appointed him Dean of Westminster.

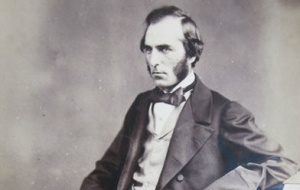

John Conington

John Conington, notable for his rather haunted expression (some contemporaries called him “the sick vulture”), first came up to Univ in 1843, but then migrated to Magdalen, where he was elected a Demy. Magdalen in the 1840s was one of the most old-fashioned Colleges in Oxford, while Univ was one of the most progressive, and eventually Conington chose to come back to Univ, where he was elected a Fellow in 1848. He left us in 1855, when he was elected the first Corpus Professor of Latin Literature. Conington was one of the foremost classicists of his day, best known for his major commentary on Virgil and the Agamemnon of Aeschylus.

Goldwin Smith

Goldwin Smith was another “refugee” from Magdalen, having been a Demy there at the same time as Conington. He was first elected a Stowell Law Fellow in 1846, at a time when this post could only be held for seven years, and was then elected to a permanent Fellowship in 1850, which he held until 1868. He was another supporter of the reform of Oxford, but also wrote extensively on current affairs. In 1858 he was appointed Regius Professor of Modern History. Within Univ., he paid for the installation of the first organ in Chapel. In 1868, Smith emigrated to North America, being one of the first professors appointed to Cornell University, and eventually settled in Toronto.

Charles Faulkner

Charles Faulkner had been an undergraduate at Pembroke College, but in 1856 was elected a Fellow of Univ., where he remained until his death in 1892. Faulkner was primarily a mathematician, but he also devoted himself to the administration of the College, serving as Bursar for many years. The diaries of his visits to College properties still make very good reading. Faulkner was also a close friend of the artists William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones. He was a witness at William Morris’s wedding, and even went into business briefly with him in the early 1860s. His sisters were also artistic, and several of their designs were used for Morris fabrics and wallpapers. In later life, Faulkner also came to espouse Morris’s socialist views.

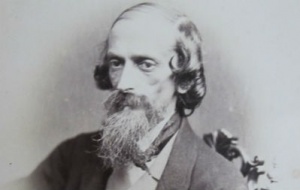

Francis Headlam

Francis Headlam came up to Univ in 1848, and was a Fellow here from 1854–74, serving as Bursar for many years. He later worked as a magistrate in Manchester. We include him here, not so much for his eminence, but rather as a cautionary example of the mid-Victorian taste for regrettable sets of side-whiskers.

Charles Abbey

This intense young man is Charles Abbey, a graduate of Lincoln College who was elected Fellow in 1862. In 1866, he resigned his Fellowship having been appointed rector of Checkendon near Henley, a College living. It had been common for a Fellow of an Oxford or Cambridge College to move to a College living after a few years, and spend the rest of his life there. Abbey was one of the very last such Fellows to make this change: by the 1860s, as ever more of our Fellows were laymen, so they no longer needed livings to go to. Abbey proved an excellent appointment: as well as fulfilling his pastoral duties to the full (his memorial in Checkendon church calls him “a living guide and friend to all”), he also coached Oxford undergraduates, and published extensively on theology. He retired from Checkendon in 1908 and died in 1915.

More information about most of these Fellows, and the life of the College during the middle of the 19th century can be found in Chapters 15 and 16 of Robin Darwall-Smith, A History of University College (Oxford, 2008).

Published: 14 March 2015

Further selected Univ Treasures are detailed below or explore the whole collection on our News and Features Treasures pages.