Unlocking some family secrets of the past

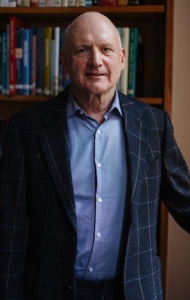

Paul Adler

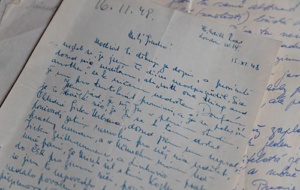

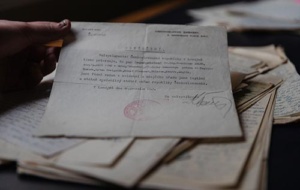

Paul Adler (1975, Physics) asked for Univ’s help to translate around sixty original letters, mostly handwritten in Czech during mid-1948 to his late Uncle Henry (1921-2007). These had been discovered in a dusty folder among Henry’s effects and relate to the chaotic postwar period as the Soviet Union established its “Iron Curtain” in East-Central Europe. The experience of those who fled nascent communist dictatorship at great personal risk, only to find themselves incarcerated in refugee camps established by the Allies in West Germany, is more thinly documented than that of those who had fled or survived the Holocaust.

In Prague, aged only twenty-six and engaged in the postwar reconstruction of his native Czechoslovakia, Henry heard that he faced imminent arrest by the communists. He escaped by hiking for three days over the mountains; crossing the border covertly to a military camp in Bavaria. Four months later he obtained the permits needed to rejoin his parents and elder brother, who had previously escaped to the UK. His willpower was forged by experiences of mortal threat and betrayal; with countervailing friendships evident from the correspondence; yet he had rarely discussed those traumatic times with his family.

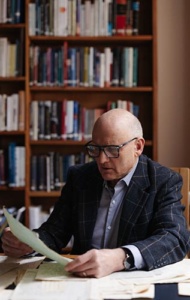

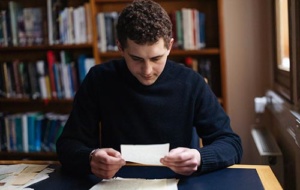

Dr Rajendra Chitnis, Ivana and Pavel Tykač Supernumerary Fellow in Czech at Univ, agreed to lead the project, which took place between June and September 2024. Two Univ students were sponsored by Paul to work on the translation: Jamie Hopkins (2023, Modern Languages – French and Czech) and Miles Bishop (2020, Modern Languages – Russian and Czech, with Slovak).

Jamie Hopkins and Miles Bishop with Paul Adler

Rajendra was able to help the students to work through the style of Czech language, particularly the slang and conventions of the times. Together they highlighted many insights as the inhabitants of the camps shared their thoughts: their plans for the future; their hopes and fears; as well as many routine preoccupations. Miles and Jamie familiarised themselves progressively with the unique character and emotions of the correspondents as each letter was translated, commenting that they felt an invisible bond develop between translator and author, notwithstanding the 75-year time gap.

It is hoped that these materials could be used by historians researching displaced populations in central Europe after the Second World War. As Professor Catherine Holmes, A.D.M. Cox Old Members’ Tutorial Fellow in Medieval History, points out, letters such as these offer precious insights into the ways that vast geopolitical changes in the past were experienced by real people. They shed light on the social and family relationships which refugees struggled to maintain in the harshest of circumstances, often over vast distances; they also reveal glimpses of the most human of emotions: frustration, fear and hope. Catherine is liaising with historians at Univ, in Oxford and beyond to integrate the letters kept by Uncle Henry into a wider research project.

It is hoped that these materials could be used by historians researching displaced populations in central Europe after the Second World War. As Professor Catherine Holmes, A.D.M. Cox Old Members’ Tutorial Fellow in Medieval History, points out, letters such as these offer precious insights into the ways that vast geopolitical changes in the past were experienced by real people. They shed light on the social and family relationships which refugees struggled to maintain in the harshest of circumstances, often over vast distances; they also reveal glimpses of the most human of emotions: frustration, fear and hope. Catherine is liaising with historians at Univ, in Oxford and beyond to integrate the letters kept by Uncle Henry into a wider research project.

The following is an extract from a conversation about the project on 30 January 2025 between Paul Adler (PA) and Rajendra Chitnis (RC).

Setting the scene

PA: Henry, who was the recipient of these Czech letters, was born just after the First World War in Teplice, Bohemia. Formerly part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, this area had just been included within the new state of Czechoslovakia.

PA: Henry, who was the recipient of these Czech letters, was born just after the First World War in Teplice, Bohemia. Formerly part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, this area had just been included within the new state of Czechoslovakia.

One gets the sense of a wonderful childhood until the growing threat from Nazi Germany, especially to those located in the Sudetenland. The family was very fortunate: my grandparents, my father and Henry all escaped to the UK during 1938-39, via separate routes.

Henry returned to Prague in 1946 with the intention to help rebuild his country following the destruction during WWII. However, Soviet influence would soon become more established across the Eastern bloc and the so-called “Iron Curtain” came down. In early 1948, under threat of imminent arrest by the Communists, Henry was obliged to escape once again. He hiked through the mountains at night and slept in ditches during the day, narrowly evading the border patrols with their dogs (they lost his scent during a heavy snowstorm).

He reached a Western military camp near Regensburg in Bavaria – and spent a further four months at various camps before obtaining the permissions needed to return to the UK. His mother (my grandmother) was shocked at his condition: perhaps 25 kilos lighter than when she had last seen him: but he had survived and was ready to rebuild his life.

RC: When you speak about things being thinly documented, it’s specifically the experiences of people like your uncle. Just this week, our subject association BASEES awarded two prizes to a book by Katarzyna Nowak called Kingdom of Barracks (McGill-Queens, 2023), which uses archival material like this to illuminate the experience of Poles in post-war refugee camps. I remember you mentioning before that your uncle didn’t want Czechoslovakia to become communist and so one of the reasons he went back was to support the idea of democratic Czechoslovakia that had existed before the war. That’s an interesting subject because Czechoslovakia was the only country in the region which voted for the Communist Party in 1946. There was a narrative that Czechoslovakia chose Communism, which I suspect your uncle would have vehemently disagreed with. It’s a very interesting period, with these questions around Henry going back and then having to flee again. One of the main reasons why he would have had to flee is because he had been in Britain during the Second World War and therefore would have been viewed with suspicion by the Soviets and by the Communist Party.

PA: We have several other documents in English (not part of this translation set) which tell us that Henry felt he couldn’t apply for a visa to leave, because that would have immediately flagged up his history. Even corresponding with someone in the West was viewed with suspicion. The Rott family appear in some of the letters: the father, a local businessman who was also the honorary Norwegian Consul, was arrested simply for becoming a member of the Czech National Social Party.

The letters

RC: Are you able to characterise generally what this fund of material was, that you gave us to translate, and who featured in it?

RC: Are you able to characterise generally what this fund of material was, that you gave us to translate, and who featured in it?

PA: The letters in the Czech language regarding the displaced peoples’ camps cover many and varied topics, ranging from the apparently trivial or mundane, to more philosophical reflection by the refugees; their hopes and fears for the postwar world. People were considering which useful skills they had, and/or which they should learn. They were desperate for reliable information, contacts and ideas for how to move on to a better future. We don’t have any of the correspondence that Henry wrote to the camps, so we have to infer what he was writing from the replies that we have.

Larger batches of family correspondence in both English and German have already provided us the wider context: this batch of roughly sixty letters is one of the final jigsaw pieces which had eluded us, since none of us has Czech language skills. Moreover, with the handwritten ones, that represents an extra level of complexity. All credit to Jamie and Miles for sticking at it and deciphering these annals with a great degree of success.

Fleeting friendships had been forged in the camps and the refugees often tried to help each other with their personal networks. However, I’m not aware that Henry later kept in touch with any of these people and he never mentioned any of this to us. Once he did write to his parents, saying, “on no account tell anybody where I am”, because he was worried that his camp was rather close to the Soviet front line and people were not sure about the political and military situation. In those early days of the “Cold War”, they didn’t know whether the Soviets would overrun more territory, or whether they might even be caught up again. There was a hesitancy to reveal his physical location and in particular, to one person whom he suspected had betrayed him during his final days in Prague.

Unexpected discoveries

RC: You mentioned about the Czech material being the last piece of the jigsaw. Are you able to say a couple of things about that? Has anything new come out of it or anything you weren’t expecting?

RC: You mentioned about the Czech material being the last piece of the jigsaw. Are you able to say a couple of things about that? Has anything new come out of it or anything you weren’t expecting?

PA: It has been enormously helpful, and we do appreciate your support Rajendra and the efforts of Jamie and Miles because these were just mystery documents.

There’s a whole range of aspects, such as people dreaming about where they could end up. Someone mentions Venezuela; people wanted to go to Italy, France, Australia or Colombia. A few of them went to were looking at Canada. There was a rich diversity of characters: people of different ages, different outlooks on life. Some could speak English, some couldn’t and were trying to learn. That was all new to me.

The more mundane aspects such as clothing, food and rations were mostly just practicalities. There’s even one letter that refers to two cigarettes, coupons and a postage stamp, which Henry had sent to his friend in one of the camps. One of the letters said they didn’t have enough money to go to the Consulate in Frankfurt by train to collect their post. So, they worked out a scheme whereby three of them would pool their resources and send one to Frankfurt to collect everybody’s mail and packages.

The letters confirm that there were like-minded, resourceful people around Henry, but not all had quite the same focus, organisation and determination as he did: the “sheer willpower” which he demonstrated throughout the rest of his life, balancing his fun-loving nature.

RC: I find it very interesting, Henry himself as the jigsaw puzzle; that you understand him or get a sense of him precisely through these sorts of details. Clearly, he was a very principled man in terms of what he wanted for his country and the kind of society he wanted to live in. But, as you say, resourceful is absolutely the key word.

I don’t know if you had a chance to see the letter I managed to translate this morning, but there was a short letter that was quite difficult for the students to read. I managed to get through it this morning and it turned out to be rather lovely. It’s from a man who calls himself Jim (one wonders if this was his real name), a Czech man and he’s in a refugee camp in Bagnoli, near Naples, waiting to be accepted by a friendly country .The first paragraph is all about how happy he is to hear from Henry. You get a sense from quite a lot of the letters that Henry tries to write letters designed to lift the spirits of people still in refugee camps. In this letter he says, “I won’t tell you how much joy it brought to me because you know how I feel.” There’s a sense of solidarity. You were here. You were in a camp like this and it was very special whenever you got positive news from a friend, that they had made it and had got to somewhere where they could start building a new life. So that’s the first thing he says. And then Jim says he’s hoping for maybe Canada, maybe Australia. And he seems in this letter to be hopeful that Australia might work out because he plays football, and this football seems to have been a good thing for him because they rate him and therefore he might get picked up by the Australians to go to Australia. The other thing is that because he’s playing football, they feed him well, so he’s not spending so much money on food!

Then there are these tiny little glimpses of what’s going on in communist Czechoslovakia and the last sentence says that somebody’s son is saying that everything is okay at home at the moment. Interesting that they refer to it as home. So, even something which at first glance looks quite banal actually has all sorts of interesting elements that help us to understand Henry specifically but help us also to understand exactly how these people were living, what they were trying to do and how they supported one another.

The other thing I liked about this, incidentally, which I’m not sure that our students would have picked up on, is that this man is clearly from Moravia, he has a different dialect in his letter. So, he speaks Czech, but it’s a bit like if we were reading a letter from somebody from Yorkshire. Which brings Jim to life even more.

Obviously, it’s incredibly special to you Paul, for building up a picture of your family and people whom you knew much later – but from our point of view, it’s making all that history that you were talking about at the beginning (the Sudetenland, the Munich agreement, and so on) come alive, when you see the human lives that were caught up in all of this.

Interestingly, in that same letter I’ve just been talking about, he tells Henry not to worry about sending any more money. So, Henry was obviously at some point sending money or trying to find ways of getting money to people. But he says, “I’d be very grateful to you if you could send in a letter one or two coupons because stamps here are devilishly expensive.” It was not only expensive to go and collect your post, but also expensive to post a letter.

PA: But amazing that it would be worthwhile sending a special letter with two stamps in it!

Letters “home”

RC: The news from “home” was not always so reassuring. One of the letters says “be happy that you have your family abroad. I received a message from my mother at home that my father has been put under arrest. This is not because of me. It’s apparently because of some kind of anti-state activity, though I believe that he may get away with it”.

RC: The news from “home” was not always so reassuring. One of the letters says “be happy that you have your family abroad. I received a message from my mother at home that my father has been put under arrest. This is not because of me. It’s apparently because of some kind of anti-state activity, though I believe that he may get away with it”.

Another letter said “father arrived yesterday evening. He tells a lot of interesting things. Discontent seems to be growing.” I assume he means discontent in Prague about the communist regime “and is present everywhere, even among the workers and soldiers. They complain that the radio here in London is too encouraging and that is not what they had during the war”. I’m not quite sure what to make of that, but it sounds as if the message that was coming out of the BBC in London didn’t gel with what people were experiencing back in Prague.

PA: Henry was disillusioned, what with the treachery and communist coup. He never went back to Czechoslovakia. He moved on, which again is part of his determined character. There’s a comment in one of the letters where he talks about “starting again and not giving in”. That was very much his philosophy. These little snippets talk to the character that that our family knew and loved.

How the project impacted on Univ’s students

RC: This sort of project is a fabulous opportunity for students. I hope that you Paul and your family understand that you have these young people coming to study Czech and, in the case of both Miles and Jamie, there was no family heritage in that part of the world. It was not an obvious subject for them to study, they hadn’t studied it before at school or anything like that, so they have a very distanced relationship to it. It’s quite theoretical at the beginning, very linguistic. We do an awful lot of work in the first year just learning the Czech language. I don’t think either of them had been to the Czech Republic before they started studying at Univ, so to come to know this place through people at an incredibly dramatic time in that country’s history is one thing. The other is obviously the opportunity to use their skills in such a meaningful way. We get them to translate all the time, but to know who the audience of these translations might be, both in terms of your family and then possible researchers after that, makes everything come together beautifully for me and it’s hugely motivating for the students.

RC: This sort of project is a fabulous opportunity for students. I hope that you Paul and your family understand that you have these young people coming to study Czech and, in the case of both Miles and Jamie, there was no family heritage in that part of the world. It was not an obvious subject for them to study, they hadn’t studied it before at school or anything like that, so they have a very distanced relationship to it. It’s quite theoretical at the beginning, very linguistic. We do an awful lot of work in the first year just learning the Czech language. I don’t think either of them had been to the Czech Republic before they started studying at Univ, so to come to know this place through people at an incredibly dramatic time in that country’s history is one thing. The other is obviously the opportunity to use their skills in such a meaningful way. We get them to translate all the time, but to know who the audience of these translations might be, both in terms of your family and then possible researchers after that, makes everything come together beautifully for me and it’s hugely motivating for the students.

PA: It’s remarkable that so much correspondence made it through at the time – never mind that it has survived for 75 years! Some of the letters overlapped in crossing and the replies were potentially quite delayed, so they may have already written two or three more letters by the time they received the reply.

RC: One of the most challenging aspects of translating this material was that these are texts written in the 1940s, often in difficult circumstances. Some of the letters have been damaged in some way or another. Certainly, somebody I think dropped a cigarette on one! As you say, it’s also the legibility of some of the letters. It’s the language, which is an older language, a 1940s Czech. They use a lot of shorthand for things that are clearly understandable to them, as anyone would at the time. I think that there will have been huge challenges to the students, to work these things out and make sense of them. When I look over them, I take quite a lot of pride in seeing the good, informed decisions the translators have made.

PA: I’d add to that, Rajendra, something that Miles explained when we had a review call. There were certain constructions or certain use of syllables that he didn’t understand in the Czech of the time. He explained how you helped him with that, and that once he understood how they talked and how the text flowed, he was able to increase his productivity dramatically on further letters.

RC: This is something that Paul and I both heard from Miles and Jamie as well, that they found this an extremely moving experience. As you start reading this material, you get used to the language, but you also start to get to know these people, because there are multiple letters by the same people. Jamie was talking about following a story of somebody who’s waiting to get out of a camp and then at a certain point, they evidently got out of the camp and there are no more letters. Jamie described it as a bit like a soap opera, that he missed that character once that character departed!

Even with the letter I translated this morning you can’t help but find it extremely moving and powerful. For modern languages students, I think this is potentially the skill you’re going to bring to the world, to bring people together in different ways. But also, you enter people’s lives, whose lives you couldn’t have imagined ever entering, and understanding what they went through.

English phrases

PA: You mentioned on a linguistic topic this morning, Rajendra, a particular letter and the way that the correspondent had woven in a phrase in English, somewhat bizarrely for 1948.

PA: You mentioned on a linguistic topic this morning, Rajendra, a particular letter and the way that the correspondent had woven in a phrase in English, somewhat bizarrely for 1948.

RC: It’s a text that’s all in handwritten Czech, except that in the first paragraph it says, so in English, the translation reads “I’m not doing anything at the moment, but” in inverted commas “with one thing and another. I haven’t got anywhere” and the “with one thing and another” is written in English. The rest of it’s all in Czech. I find these details very interesting because there’s not an exact Czech translation of “with one thing and another”. Clearly this Czech person had found this phrase in English rather an attractive and useful phrase, “with one thing and another”, referring to fleeing Czechoslovakia! This tendency to understate things is something Czechs and Brits share. It also shows that this person is now increasingly working in English or using English a lot, and so these phrases are falling into the way they speak, which of course we’re familiar with, with people who come here.

PA: Thanks for that explanation. It took your eye to pick that up because I just glossed over it.

In one paragraph they refer to coded letters that they exchanged with family, if they were still in Czechoslovakia. It didn’t jump out at me but bear in mind that they were theoretically all safe, both the sender and receiver at that point. They may have been frustrated because they were in a military or refugee camp, a displaced persons camp: but it was still in the West. Certainly, Henry in that letter saying, “on no account tell people where I am”. They were certainly conscious of it, but I bow to your judgement, Rajendra, as to whether there was any deeper code in the letters.

RC: I’m not a historian; I’m not a specialist on this period. I had a student who wrote a PhD which is now a book on the BBC’s Czech-language broadcasts to the occupied Protectorate (Erica Harrison, Radio and the Performance of Government: Broadcasting by the Czechoslovaks in exile in London, 1939–1945). It’s in the period just before this. A lot of these broadcasts relate to the Czechoslovak pilots who were fighting in the Battle of Britain, and there are many purposes to this, including to tell people back home that the Czechs and Slovaks are participating in the war, that they’re fighting, as indeed Henry was, and fighting against the Germans. She picked out a passage where you can hear that it is at an airfield and the pilots are coming off the planes. They interview the pilots and ask them: “What are you going to do now?” The pilots say: “We’re going to have breakfast.” “What are you going to have for breakfast?” They reply: “Oh, we’re going to have scrambled eggs and then we’re going to have toast, and then we’re going to have tea” Then the reporter says: “Is that the last meal you’ll get today?” “Oh, no. Later we’ll have dinner, a main meal in the middle of the day”. “And what will you have?” “We’ll have meat and vegetables and potatoes.” It sounds very odd, the description seems too detailed. Erica worked out that this was because the Nazi propaganda in the Protectorate claimed that the British were not looking after these people well, and therefore they wanted to communicate that things were all right! It is on a slightly different point, which is not so much necessarily speaking in code, but providing very specific information to respond to rumours and reassure people perhaps. I also detect a little bit of that in Henry’s letters, particularly the idea of keeping people’s spirits up, sounding positive and optimistic. You can see that the circumstances that they’re living in are very difficult, but the tone of the letters is one of solidarity and looking after one another, and that it will all be all right. I wonder whether some of that is a sort of code as well.

PA: Indeed, it refers to one of the paragraphs we pulled out about the communications from London being unduly optimistic compared to what people felt back in Czechoslovakia.

RC: This is clearly going to be the work that a researcher might pick up, someone who perhaps has a larger body of this sort of material. What we’re missing are more examples of letters that went from the family into Czechoslovakia, or from these people into Czechoslovakia in this period, and how those communications worked. I think there will be researchers who have access to some of those things, and if they add this material into that, they’ll illuminate each other.

Support for refugees

PA: Rajendra, you kindly sent me two months ago a study which was written about the camps. That was quite harrowing, explaining in gruesome detail some of the circumstances of people surviving there. I’m not clear whether those were civilian camps and Henry was relatively more privileged because he’d been in uniform. It may even have been that they continued in their military uniforms, in the camps.

PA: Rajendra, you kindly sent me two months ago a study which was written about the camps. That was quite harrowing, explaining in gruesome detail some of the circumstances of people surviving there. I’m not clear whether those were civilian camps and Henry was relatively more privileged because he’d been in uniform. It may even have been that they continued in their military uniforms, in the camps.

RC: I wonder whether the fact that Henry had already been in Britain meant that he was either better connected or he just had a better sense of how things worked and what organisations there were in Britain and so on. Again, we don’t hear his voice, of course, because we don’t have his letters, but you get a sense that he’s seen as an authority by the people who write to him. A lot of it is not so much about money or about material help, it’s about, “whom should I contact now? This hasn’t worked.”

PA: He also had the benefit, of course, which few of the others had, that his parents were already working in the UK: they were earning and contributing to British society. That probably helped a little when it came to visas. With many of the other correspondents, it didn’t seem as though they had anywhere near the same kind of positive reasons to be repatriated.

RC: That’s right. The other thing from what you’re saying, Paul, and I remember that the students commented on this particularly as well, is that we’re all familiar with the powerful national narrative Britain has about us being a tolerant country, a country that receives refugees and helps people. But when you read these accounts, that’s not really the picture that you get of what’s happening. It is far more dependent on the resourcefulness of these people and their informal support networks to solve their problems. They are being kept often in appalling conditions; they have limited amounts of food and hygiene. The article to which you refer is mainly about medicine and hygiene. You don’t get the sense that the countries are falling over themselves to take these people.

Is it the Rotts who were working with the United Nations or something like that in some of the letters? Růžka, which is Rosie, (Růžena would have been her full name) seems to have acted in a charitable role helping refugees in Scandinavia and supporting them.

PA: Yes, Mr Rott had been Honorary Norwegian Consul in Prague, where the two families were very close. They escaped to Scandinavia (in early 1948 with Henry’s help); Mrs Rott was then helping more people, both to get there and I think specifically to sort themselves out when they are there, to have enough to live on. She was complaining because they sent a train or coaches for 100 young people to come to Scandinavia and only 49 turned up. She was scandalised that they couldn’t get themselves organised to fill up the transport. I can’t remember what the explanation was, but she was upset because the carefully planned arrangements hadn’t been fully taken up.

It’s quite interesting: you would get the main text, maybe two pages, from Mr Rott in most of the cases and then Mrs Rott would add just two lines at the end “I too send my warmest greetings etc. Best regards, Růžka.” In my own childhood it was my grandmother Ilse, Henry’s mother, who would write to me with her news at some length, concluding “here’s something for your birthday” or “hope you’re having a lovely time” and then my grandfather would add his two lines “I also send my warm regards. Best wishes, Franz.” There would be one main correspondent, but not to be left out, the spouse would add a little coda!

RC: Clearly this is a Europe which has now had nearly a decade of camps, of people being moved and the concentration camps and prisoner of war camps during the Second World War, but then the camps for displaced people after the war, including camps for the Bohemian Germans who were expelled from Czechoslovakia after the war. Camps were a phenomenon of Europe in this period. The other thing to say in mitigation of these governments, is that some of these countries are formerly occupied countries that are trying to rebuild themselves, or Britain, which has been heavily bombed, and so on. They’ve got an awful lot on their plate. I wouldn’t want to phrase it too unkindly, but it is very clear that the refugees are just one of a million problems they are trying to solve.

PA: There were organisations in the UK, often run by exiled Czechs, such as The British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia, which were immensely helpful. By providing funds for people when they arrived, they could reassure both Parliament and the Home Office that accepting such refugees would place no burden on the British State: “Please just issue the visas and we’ll take care of everything else.”

Looking to the future

RC: We didn’t have any model to follow for this project; we made it up as we went along. Going back to the beginning of this conversation when we were talking about how this all started, I think you met Professor Catherine Holmes, A.D.M. Cox Old Members’ Tutorial Fellow in Medieval History, at a Univ North Tour, is that right?

RC: We didn’t have any model to follow for this project; we made it up as we went along. Going back to the beginning of this conversation when we were talking about how this all started, I think you met Professor Catherine Holmes, A.D.M. Cox Old Members’ Tutorial Fellow in Medieval History, at a Univ North Tour, is that right?

PA: I did, but actually I had first engaged with you, Rajendra, during the COVID-19 pandemic when you presented a virtual talk and Q&A for members of the College. Initially you didn’t have any students who would be suitable, and it was all very difficult during lockdown, particularly as nobody was in College at the time. It was two years later that I picked up with Catherine and said, “we had this conversation with Rajendra, should we give it another shot?” She also had some personal contacts at other universities. As it’s not close enough to Catherine’s research, or that of our other history Fellows, we might want to consider introducing a third party.

RC: Absolutely. I agree with that. When we rounded off the project in the autumn, I met Catherine and, as you say, I think the basic problem is that this isn’t what the historians at Univ work on, but that doesn’t matter really. Before we start talking about external partners, I think the point is that our postgraduate historians at Univ have to write dissertations, and this is exactly the sort of body of material which is very well defined. As we’ve discussed, there are several different angles that one could approach this material from. It would be a great training experience for a student to work with an archive like this and produce something very meaningful, in a different sense for my students, you know, in producing what historians can do. That’s very much our hope and what Catherine and I spoke about. The trick really, as she was saying, is to make sure that historians who work in this period are made aware of this resource, and I think that’s what she’s been doing within Oxford and beyond. The loveliest thing would be if there’s a Univ historian who happens to be being supervised by somebody at another college but nevertheless has a Univ archive to look at for their work.

PA: Catherine was very positive and said we need to know what these letters said. A key building block has now been put in place. We don’t have firm plans for the next couple of years, but let’s try and keep an open mind as to where it could land.

Biographies

Paul Adler (1975, Physics) is a retired Company Director. He started out in engineering and IT roles. Progressing into management consultancy, he became a partner at Accenture plc. He then founded and built up a specialist consultancy focused on knowledge management, collaborating on international projects with the Oxford University Department of Computer Science. He has twice cycled over the Alps in aid of charity and later this year will tackle the Manaslu Circuit, a 15-day high altitude trek in Nepal (following in Henry’s footsteps).

Dr Rajendra Chitnis, Ivana and Pavel Tykač Supernumerary Fellow in Czech at Univ, teaches classes in Czech and Slovak literature from the fourteenth century to the present, and translation from Czech and Slovak into English. His most recent publications include a major study of the earliest published Czech writing about the experience of the German occupation (‘The Silence of the Occupied in Czech Literature, 1940–46’, Slavic Review, 81 (2022), pp.701-721).