John Ruskin’s drawings

This year is of course a huge anniversary for the College, what with us celebrating 775 years of Univ. But 2024 also marks 225 years since the birth of artist and critic John Ruskin. Ruskin was closely associated with Oxford during his life; he was an undergraduate at Christ Church from 1836 – 1842 and, 27 years after graduating, was appointed as the first Slade Professor of Fine Art in 1869. Many buildings in the city still bear his name. One such is the Ruskin School of Art, Univ’s neighbour on the High Street since 1975.

This year is of course a huge anniversary for the College, what with us celebrating 775 years of Univ. But 2024 also marks 225 years since the birth of artist and critic John Ruskin. Ruskin was closely associated with Oxford during his life; he was an undergraduate at Christ Church from 1836 – 1842 and, 27 years after graduating, was appointed as the first Slade Professor of Fine Art in 1869. Many buildings in the city still bear his name. One such is the Ruskin School of Art, Univ’s neighbour on the High Street since 1975.

Univ has no direct relationship with Ruskin, but amongst the College’s treasures we have two rather special examples of the artist’s work. These are two sketches, presented to the College in 1932, that the artist produced as a young man; one made before he matriculated and the other before he had graduated. Curiously, the College has never made much hullabaloo about us having these pictures, despite their rarity and attractiveness. While they had previously hung in the former Academic Office, they have, for a number of years now, been kept out of public view in our Archive. We hope this Treasure will bring some renewed attention to these very charming pictures.

We will answer the question of how these sketches came to Univ later in this Treasure.

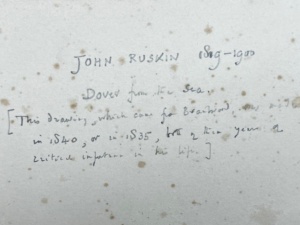

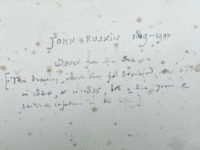

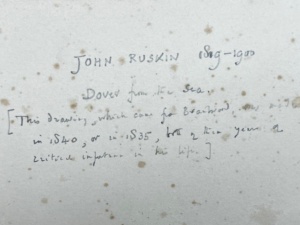

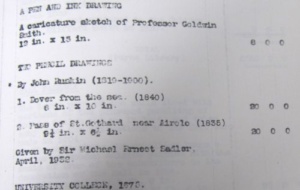

Sadler's note

John Ruskin 1891 – 1900

First, a note pencilled on one of the frames, written by the former Master, Michael Sadler, gives a neat insight into where they came from. It reads:

“John Ruskin 1891 – 1900 Dover from the sea

This drawing, which came from Brantwood, was made in 1840, or in 1835, both of these years of critical importance in his life.”

Brantwood House was Ruskin’s Lake District home from 1871 until his death in 1900. Ruskin’s will was executed by his second cousin, Joan Severn, and his secretary, W.G. Collingwood, and his enormous collection of written works was edited into 39 published volumes. Within a few decades after his death, Ruskin’s reputation had waned and, prior to the selling of Brantwood in 1934, his belongings were auctioned off. Univ’s pictures were purchased at a 1931 auction. Information regarding when the sketches were made came from Brantwood, and the College’s only record of these details springs from the above note. Therefore, we cannot be certain how the sketches have been dated. But, in exploring a little of Ruskin’s biography, we can see that they depict scenes that fit into and illustrate what we know of his life during this period.

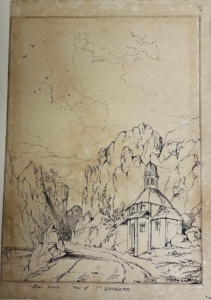

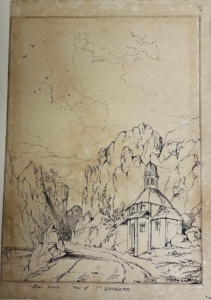

Pass of St. Gothard

The first sketch is the “Pass of St. Gothard near Airolo,” dated to 1835 when Ruskin was only 16 years old. The Gotthard Pass winds through the Alps, connecting the north of Switzerland to the south. We can identify with good accuracy the period when Ruskin would have travelled to Switzerland and produced this sketch. With his parents alongside him, in 1835 Ruskin embarked on a long tour of the continent during which he produced a tremendous amount of work. He wrote a substantial travel journal and copious amounts of poetry, in addition to many sketches of the landscapes he observed. In the ‘Library Edition’ of Ruskin’s written works, his output from 1835 constitutes around a fifth of the overall texts. Sadler’s note that this year was a critical one for Ruskin is somewhat understated.

Evident in this sketch is Ruskin’s confidence in his own talent. This may be thanks in part due his tutelage; by this age he had already been the pupil of Charles Runciman (Runciman’s lessons would be published in his daughter’s book, “Rules of Perspective,” for which Ruskin wrote the foreword) and of the celebrated English artist Copley Fielding. But even in this early work, Ruskin’s philosophy that art should represent the truth of nature is evident.

Gotthard Pass also inspired J.M.W. Turner, who, in 1803-4, painted “The Teufelsbrücke, St. Gotthard” (The Devil’s Bridge). Turner benefitted from the patronage of Ruskin and his father from the early 1830s until the artist’s death in 1851. Ruskin and Turner first met in June 1840, the other critical year as identified by Sadler. The pair maintained a professional— and somewhat personal, allowing for the social awkwardness of both men— relationship for the next decade. Ruskin junior was even appointed as an executor of Turner’s will, although he would quickly regret this role upon discovering the knottiness of Turner’s testament (and studio contents). For years after Turner’s death, Ruskin was cataloguing and conserving some 19,000 of his drawings that had been left to the nation.

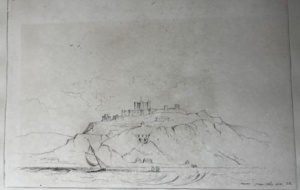

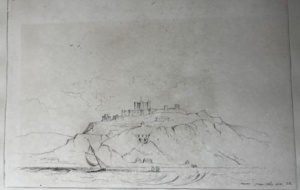

Dover from the Sea

Our second sketch is titled “Dover from the Sea,” and has been dated to 1840. The Ruskin family travelled often and would have set sail from Dover regularly. In his written works, Ruskin remarked upon a trip to Dover he had taken in 1829, aged ten. He loved looking at the sea during this journey and “spent four or five hours every day simply staring and wondering [at its] tumbling and creaming strength.” His observational skills are evident here, as the simple composition and unembellished marks capture at once the choppy waters and peaceful cliff face, while Dover Castle shrinks into the distance as the artist sails toward Europe.

This sketch would have been produced during one of those prolonged holidays with his parents. In April 1840, while studying for his exams, Ruskin was forced to suspend his studies at Oxford for over a year due to poor health. He had suffered a particularly bad bout of illness which included coughing up blood. Suspecting tuberculosis, his parents extracted him from Oxford and the family rapidly fled to Dover and passage to European climes.

The cause of this sudden illness coincided with (and his parents attributed it to) Ruskin learning that his unrequited love, Adèle Domecq, had married. Ruskin had been woefully infatuated with Adèle since he was 17, but the younger woman possessed a derisively cool, Parisienne worldliness. A match with the clumsy and sheltered Ruskin was never likely. This would prove to be the first of several ruinous infatuations with younger women.

Ill health had dogged Ruskin throughout his adolescence, and he would suffer prolonged periods of melancholia until his death. Ostensibly to monitor her son’s health and spirits while at University, in 1836 Mother Ruskin followed him to Oxford. It is unclear how much of a say Ruskin had in this development. Regardless, Margaret Ruskin moved into the lodgings at 90 High Street, which she would sublet for the next several years. Univ’s College Record, in detailing the acquisition of the sketches, notes that John Ruskin “spent part of every day in term time 1836 – 1842 with his mother at 90 High Street.” Owing to the mother and son’s closeness this may indeed be true, but Ruskin’s nominal dormitory was in Christ Church’s Peckwater Quad.

90 High Street has been part of Univ’s main site since the College acquired it in 1905, but the Ruskins’ occupation occurred while it was still owned by Christ Church. It is, however, a charming coincidence of fate that Univ should acquire both Ruskin’s formative artworks and his former room when his mother’s fussing was an integral feature of both.

Now, onto the question of how these drawings came to be in our collections. It was the acquisition of 90 High Street that proved the instigating factor, as through that purchase Ruskin’s former dwelling became a part of Univ’s history. The drawings were gifted to College in 1932, 17 years and two Masters later. Michael Sadler, Master from 1923-1934, was an enthusiastic art collector and it was he who purchased the drawings to fasten the Ruskin connection in a tangible form. In acknowledging the gift, the College Record states simply that the pair was given by “a member of the College,” but this wording is due to the fact Sadler edited the Record and he was routinely modest in documenting his contributions. Harold Clifford Smith’s 1943 inventory of College chattels definitively names Sadler as the donor.

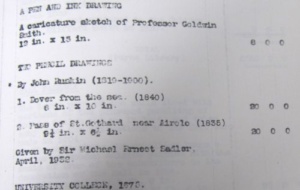

Inventory p. 57

Sadler was likely very pleased to purchase the drawings, as he had been a student at Oxford in the 1880s and in these formative years had been greatly inspired by Ruskin’s thoughts on philosophy, politics, and education. Ruskin was an esteemed personality in Oxford by this time and he maintained much business throughout the city; he operated as the Slade Professor of Fine Art from 1869-1879, and again from 1883-1884, and oversaw his Ruskin School of Drawing (now the Ruskin School of Art, part of the University of Oxford). In between fallouts with the University, he delivered several series of lectures on myriad topics, all of which were massively oversubscribed. In 1881 or 1882, while an undergraduate at Trinity College, Sadler manged to secure a coveted ticket to see Ruskin lecture at the Oxford University Museum (now the Oxford University Natural History Museum). Ruskin’s ideas influenced Sadler’s philosophical and political approach to his work as an educationist, so it must have been pleasing to endow a tangible connection between the man he so admired and the College he had served.

Michael Sadler did a great deal for Univ. It is thanks to his liberal-mindedness that Univ Library acquired the Robert Ross Memorial Collection of Oscar Wilde publications and ephemera, as Sadler saw the artistic and scholarly value the collection when other institutions could not. Ruskin’s drawings are delicately beautiful additions to Univ’s collections, and the twists of fate that would weave Ruskin into Univ’s history make it especially charming that we should have them.

Bibliography

Pass of St. Gotgard by John Ruskin, 1835.

Dover by the sea by John Ruskin, 1840.

University College Record, 1932-33.

Inventory of Chattels, University College, 1943.

John Batchelor, John Ruskin : No Wealth but Life : A Biography (London, 2001).

Robert Hewison, John Ruskin (Oxford, 2007).

John Ruskin, The Works of John Ruskin, eds. Edward Tyas Cook and Alexander D. O. Wedderburn (1903-1912).

Michael Sadleir, Michael Ernest Sadler, Sir Michael Sadler K.C.S.I., 1861-1943 : A Memoir by His Son (London, 1949).

William Smart and J. A. Hobson, John Ruskin, His Life and Work ; and, John Ruskin, Social Reformer (London, 1994).

Further selected Univ Treasures are detailed below or explore the whole collection on our News and Features Treasures pages.

Published: 4 June 2024

Explore Univ on social media

This year is of course a huge anniversary for the College, what with us celebrating 775 years of Univ. But 2024 also marks 225 years since the birth of artist and critic John Ruskin. Ruskin was closely associated with Oxford during his life; he was an undergraduate at Christ Church from 1836 – 1842 and, 27 years after graduating, was appointed as the first Slade Professor of Fine Art in 1869. Many buildings in the city still bear his name. One such is the Ruskin School of Art, Univ’s neighbour on the High Street since 1975.

This year is of course a huge anniversary for the College, what with us celebrating 775 years of Univ. But 2024 also marks 225 years since the birth of artist and critic John Ruskin. Ruskin was closely associated with Oxford during his life; he was an undergraduate at Christ Church from 1836 – 1842 and, 27 years after graduating, was appointed as the first Slade Professor of Fine Art in 1869. Many buildings in the city still bear his name. One such is the Ruskin School of Art, Univ’s neighbour on the High Street since 1975.