Grave matters

Fig.1 Grave marker for James Griffith

With All Souls Day coming up on 2 November, this month’s Treasure is an unusual one: we encourage you to think about an important aspect of the interior of the Chapel, namely what lies beneath it.

As well as being the centre of Christian worship within the College, Univ.’s Chapel was also, for the first two centuries of its existence, a place of burial. Like other Oxford College Chapels, Masters, Fellows and undergraduates were buried here, especially if they had died in College. We know of at least a dozen people who were buried in the Chapel, and there will have been several others.

Fig.2 Grave marker for Nathan Wetherell

In death as in life, there was a hierarchy of burial places within the Chapel. Therefore it was only Masters who were buried under the altar. Four of them are known to lie there, all marked by simple stones. Here (Fig. 1) is the grave marker for James Griffith, Master from 1808-21, who sent Percy Shelley down, and who is the subject of our August, 2014 Treasure.

Alongside James Griffith lies his predecessor, Nathan Wetherell (Fig. 2), who was elected Master in 1764 and died in 1807, and remains the longest-serving holder of the post.

Fig.3 Monument to Nathan Wetherell

Unlike Griffith, however, Wetherell’s family could also afford to erect a grand monument in his memory (Fig. 3). This now hangs in the Antechapel, to one’s left as one enters. Wetherell died a rich man, and his family could afford the very best for him: this fine memorial is the work of the great neo-classical sculptor of the day, John Flaxman, who had earlier created the memorial to Sir William Jones. Originally this memorial was erected on the south side of the altar, looking over Wetherell’s grave, but when the current extra window was installed there in 1862, the memorial was moved to its current position.

Other members of the College were buried in the Antechapel, and a few grave markers to them are still just visible.

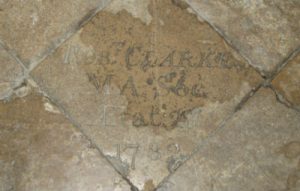

Fig.4 Grave marker for Robert Clarke

Fig. 4, for example, is the stone marking the grave of Robert Clarke, elected Fellow in 1777, who died aged only 28 in 1782. It lies not far from the First World War Memorial. Clarke was Bursar when he died, and several of his papers survive in the archives (see Papers of Former Fellows under Online Catalogues on our Archives page), which shed much light on how the College was run in his time. This plain marker suggests that Clarke’s family could not afford much, but at least they made sure he was commemorated here.

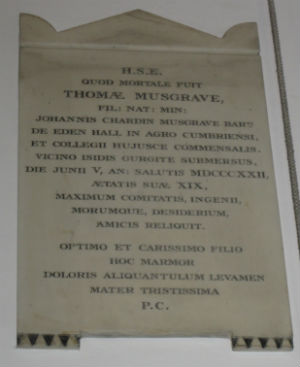

Fig.5 monument to Thomas Musgrave

Another monument to premature death hangs just under the organ (Fig. 5). This sober but elegant memorial commemorates Thomas Musgrave, the youngest son of a baronet, who came up in 1819, and was drowned in the Isis in June 1822, when, during Eights Week, he accidentally fell over the side of a boat. He was 20 years old. Although there is no grave marker for Thomas, the fact that the inscription on the memorial reads “here is buried that which was mortal of Thomas Musgrave” suggests that his mother, who commissioned it, decided that he should be buried in his College rather than at home.

A few decades after Thomas Musgrave’s death, concern was growing in Britain over the possible dangers to health caused by overstuffed churchyards in inner cities: there were many unpleasant stories of the difficulties experienced in trying to clear space in them for fresh burials. Oxford was not immune from such concerns, and in 1855 all burials in Oxford city churchyards were forbidden: in future the citizens of Oxford could only be buried in cemeteries on the edge of the city.

Fig.6 Gravestone for Frederick Plumptre

It is not clear whether this order affected burials in chapels in the Oxford Colleges. However, Univ did manage one more burial within its walls, namely for Frederick Plumptre, who was our Master from 1836–70. Plumptre had given his whole life to Univ, having first come up as an undergraduate in 1813, and he died in office. The Times of 26 November, in reporting his funeral, explicitly says that he was buried in the College Chapel, and there is a fine gravestone to him right in the middle of the Antechapel (Fig. 6).

Fig.7 Monument to Edwin Arnold

Plumptre appears to have been the last person actually buried in our Chapel. There is, however, one more member of the College whose remains lie here. This is the poet, journalist and orientalist Sir Edwin Arnold, who came up in 1850. When he died in 1904, the College permitted his family to place an urn containing his ashes in a niche in the Antechapel (Fig. 7), which stands next to the Second World War Memorial. This is the only interment of ashes to have taken place within the Chapel.

Published: 14 October 2015

Further selected Univ Treasures are detailed below or explore the whole collection on our News and Features Treasures pages.