Threads of History

Univ first year historians had the opportunity to get an advanced view of an exhibition coming to the Ashmolean Museum this September on “Colour Revolution: Victorian Art, Fashion and Design”. Meeting with curators Matthew Winterbottom and Maddie Hewitson, we explored key themes in nineteenth-century history by following the (very brightly coloured) threads of the story of synthetic dyes.

Univ first year historians had the opportunity to get an advanced view of an exhibition coming to the Ashmolean Museum this September on “Colour Revolution: Victorian Art, Fashion and Design”. Meeting with curators Matthew Winterbottom and Maddie Hewitson, we explored key themes in nineteenth-century history by following the (very brightly coloured) threads of the story of synthetic dyes.

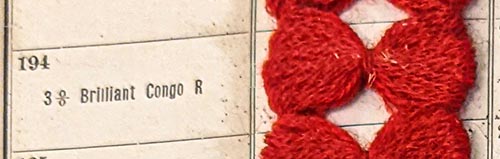

Bismarck brown and Brilliant Congo are not names of colours familiar to the wider public today. Those with an interest in nineteenth-century history might get the chemists’ in-joke in naming a rust-coloured shade after Germany’s Iron Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck. The imperial connotations of the Congo reference are perhaps more immediately obvious. This triumphant flame red heralded the 1884-85 Berlin Conference. Here, representatives of the European powers recognised Belgian King Leopold II as the owner and ruler of Congo Free State, and, in the absence of any African representatives, paved the way for the partition of the rest of the continent amongst themselves. Other shades have become so well known that they are now identified primarily as colours, rather than as places or historical events. Pinkish-purple Magenta is one of the four colours used in inkjet printers. Originally called fuchsine, it was renamed to celebrate the French-Sardinian victory over the Austrians at the Battle of Magenta in 1859, a key moment in Italian reunification.

Naming has always been an intensely political act. In the late nineteenth-century, newly invented aniline dyes were imbued with ideas about imperialism and nationalism. Whilst the conditions of their invention reflect transnational European collaboration, as chemists worked across borders and shared ideas and techniques, intense national rivalries were also expressed through wars of patents and competing appellations. The entanglements of technological innovation and imperialism are demonstrated by how the very first aniline dye was discovered. In 1856, a young British chemist, William Henry Perkin, who had studied under the German chemist August Wilhelm von Hofmann, was attempting to synthesise quinine from coal tar. Quinine, which could only be found in the bark of the South American cinchona tree, was used to treat malaria, a disease whose effects were impeding European imperial expansion in Africa. Perkin failed to synthesise quinine, but instead accidently produced a synthetic dye – mauveine.

The effects of this were far-reaching. Purple had previously been a colour reserved for the rich. It was expensive, complicated and smelly to produce, the dye made from murex sea snails, and more specifically mucous glands located by the snails’ rectum. Now, purple was democratised. Working-class and middle-class women could afford purple and other brightly coloured clothes made with synthetic dyes, leading to an explosion of colour and – because everyone was wearing them – the development of ideas about ‘garishness’ and ‘tackiness’. Particular panic was induced when such colours were accessorised with the feathers of male birds such as male peacock plumage – whose function, Charles Darwin had recently argued, was to facilitate sexual selection. European men took to wearing much more dour blacks and browns outside the home, to signal their seriousness and industriousness. Bright colours on men and in paintings came to be associated with ‘the Orient’, depicted as exotic and indolent, alluring and uncivilised.

Synthetic dyes destroyed the natural dye industry, based on plants and animals. In India, a preeminent producer of the latter, this was a blow to the colonial economy. In Bengal, European, mainly British, entrepreneurs, alongside a handful of smaller-scale Bengali businessmen, had made huge fortunes controlling the fields and factories which produced natural indigo. Whilst this created rural employment, indigo became hated, producing little income for Indian peasant producers and competing with the cultivation of subsistence foodstuffs and more profitable market crops. In the 1850s, there were a series of revolts against forced indigo growing and the production of natural indigo became a nationalist symbol of the ills of colonialism. Large-scale planters and factory owners, supported by parts of the colonial administration, fought to defend natural indigo against synthetic dyes and harness science on their own terms to improve its yield and quality. By the start of the twentieth century, however, demand for natural indigo was in sharp decline, worsening further the conditions of Indian peasant producers. In 1917, the first satyagraha (non-violent resistance) movement led by Mahatma Gandhi took place in the Champaran district of Bihar, focused on the exploitation of indigo-producing farmers.

Indigo was, in fact, one of the last colours to be successfully synthesised, and it was German chemists who successfully did so and launched it onto the market in 1897. By the late nineteenth century, Germany had emerged as the world leader in the production of synthetic dyes, the result of close ties between academic and industrial chemists, investment in technical education and research and its patent law. On the eve of the First World War, Britain no longer produced khaki dye, and initially was forced to secretly import it from Germany.

The talk and tour at the Ashmolean were of particular interest to first-year students taking the modules European and World History from 1815 to 1914 (Society, Nation and Empire), History of the British Isles 1830-1951 and Approaches to History. What the talk and tour brilliantly demonstrated is the many ways in which we can study history. The development of synthetic colour provides a way into analysing industrialisation and economic history, class hierarchies, women’s history, the construction of ideas about femininity and masculinity, imperial history, the history of nationalism and the history of science. It helps us to see the interconnections between these different themes and approaches. It also enables us to think about scales of history, exploring the relationship of individuals to the societies in which they lived, and the national and global shifts taking place around them.

Dr Natalya Benkhaled-Vince, Sanderson Tutorial Fellow in Modern History.

Colour Revolution opens at the Ashmolean on 21 September, 2023 – see ashmolean.org

For more information on the nineteenth-century chromatic turn, have a look at the Chromotope project and find out more about studying history at Univ.

Published: 3 March 2023